In her book, ‘Preserving The Past’, Delhi-based journalist, Meha Mathur, takes readers through the history of heritage laws in India. From quoting ancient texts on conservation methods to current laws governing monuments in various Indian cities, the book, provides interesting insights for history and heritage enthusiasts. Meha has over three decades of experience as a print journalist and she is a post graduate in History from Delhi University. In this interview she speaks about her own childhood bonds with historical monuments and the learnings, she gained while writing the book.

What do monuments mean to you and how have they shaped your life?

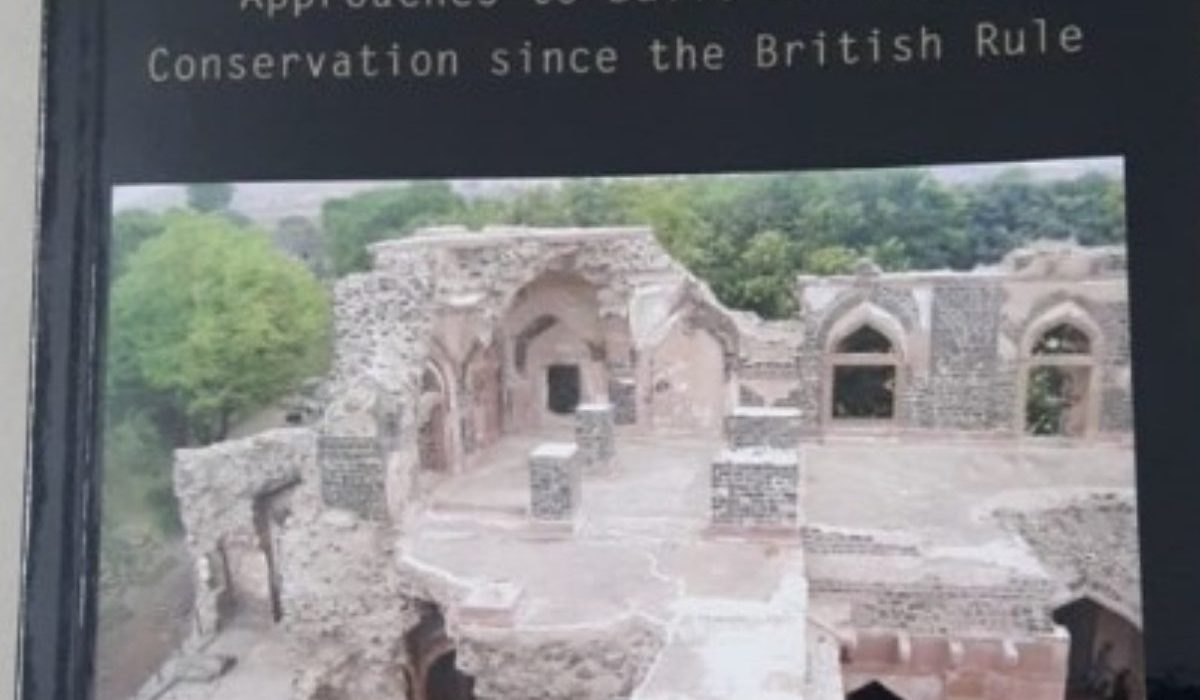

Looking back my fascination with old buildings began in 1983, when as a teenager my family relocated from Indore, Madhya Pradesh to Delhi. Equipped with a detailed map of monuments published by the Archaeological Survey of India, we scoured every nook and corner of Delhi over the next few years, including sites that were rarely frequented then. This opened up, a whole new world before me. I took to these explorations like a fish takes to water.

A dynamic teacher in high school further cemented my love for all things past. By then it was absolutely clear what I loved doing the most—exploring ruins, which later also led me to study history. Even today, I revel in wild growths. To me they represent mystery. Old buildings with patina give a strange solace, a sense of continuity between past and presence and evoke a sense of wonder about the people who inhabited these buildings.

What inspired you to write Preserving the Past?

I would not use the word ‘inspiration’, rather, this book is a logical milestone in my quest to return to my original passion– History. I graduated in the subject from St Stephen’s College and did masters from Delhi University in Ancient History. But then, for certain reasons, deviated from the path, to join print media.

While working in an education magazine, answering career queries of youngsters led me to the decision that whatever guidance I can provide in future to them should come from a point of having done some value creating work in the field of my choice.

This was a defining moment, and since then, I have been on a journey of self-discovery. In my spare time, I would set out on heritage trails to enrich my knowledge about the past. This was also the time when Ramachandra Guha wrote his tome India after Gandhi, Rajmohan Gandhi wrote Mohandas, and William Dalrymple wrote The Last Mughal. Reading these books and many others increased my understanding of the subject.

Working with India Legal magazine a few years ago, I got the opportunity to write extensive articles on legal judgments. Once such feature on efficacy of laws pertaining to built heritage sowed the seed for the present book. In 2019, doing a course in research methodology at Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), New Delhi, convinced me that this subject matter could be the premise of a book. My career journey has brought me to this point where I have been able to combine my passion for heritage, my worldview and my media experience.

What striking discoveries and disappointments did you encounter about heritage laws and people’s perceptions about built heritage while writing the book?

I was fascinated by laws against vandalism of buildings in the ancient world, and the detailed discourse on this theme over centuries in the West. To a student of history, researching about British explorers such as James Prinsep and James Fergusson, who were in fact administrators, was also a revelation. As to the laws, I realized that they are adequate, what disappointed me was the apathy at several levels. Authorities turning a blind eye when unauthorised constructions take place, governments seeking to demolish heritage buildings ( for instance the case of Errum Manzil, Hyderabad, which was mercifully saved by the judiciary); real estate pressures and tweaking of rules to suit the situation (such as the case of downgrading the status of Old Kenilworth Hotel, Kolkata, to facilitate its demolition) and differing notions of what should be preserved and what is dispensable (in the case of the Hall of Nations in Pragati Maidan, New Delhi). The struggle of Heritage Beku, a group comprising heritage lovers, environmentalists and other concerned individuals in Bengaluru to preserve not just heritage structures but also the green spaces and overall ethos of the city touched a chord with me. With land being at a premium, heritage and development are postured as being at loggerheads, but through heritage-led interventions the two interests can be brought on the same page.

In bustling and historic metropolises like Delhi and Mumbai, how according to you, can heritage and development go hand in hand?

In these cities, as well as in other cities, monuments of national importance get due care (although even there, we do find violations. For example, on December 23, 2020, the Delhi High Court, hearing a plea regarding an unauthorised construction within the 100m prohibited area around Qutub Minar, directed the ASI and South Delhi Municipal Corporation (SDMC) to fix responsibility for the lapse).

In the case of Delhi, which has monuments of lesser importance all over the city, these have been positioned as green spaces, places of recreation and rejuvenation. When people develop a connection with these spaces, they also develop a stake in preserving these structures.

But the main challenge exists in terms of listed heritage buildings, which are not of national importance, but they represent architectural or aesthetic merit, or cultural or historical significance for the community. Now, these might be someone’s residence too. Why should that person sacrifice his aspirations for the sake of heritage lovers, is the moot question.

Hence, the need for arriving at a middle ground, wherein the façade is maintained but other modifications are allowed. Financial incentives to the owners should be provided so that they are motivated to preserve the heritage value of the building. Expert involvement for overseeing major modifications such as plumbing and refurbishing changes, to safeguard the structure should also be offered.

Which Indian monument to you stood out in terms of including best conservation practices?

Rather than a monument, I would like to mention the success story of Rajasthan in

adaptive reuse. To quote from the concluding chapter in the book: “With its rich cultural heritage, both built heritage and folk arts, its old-world charm has been thrown open to tourists. The palaces and forts in the state now function as hotels, drawing large number of tourists, creating avenues for revenue generation and employment too. The money thus earned can be utilised for the upkeep of properties too.”

#bookhistoryindia, #heritagelawsofindia, #indiaheritage, #mehamathur, #preservingthepast